SignPath integrates with other systems, so we have to understand how they work and what the security attributes of certain features are. Any over-reliance on implicit or explicit security guarantees might effect the entire code signing process.

For this reason, we routinely analyze not only our own software and services, but also certain features of third party systems.

In our analysis of AppVeyor, we looked at the encryption of secrets, such as SignPath API tokens. Note that what we have discovered is not an exploitable security issue, but we thought the entire analysis still makes a good read for people interested in application security.

SignPath integrates with AppVeyor builds to verify the origin of build artifacts before they are signed. We recently investigated AppVeyor’s “secure variables” (aka “Encrypt YAML”) feature. We discovered a few interesting things, which we describe in this blog post.

AppVeyors Secure Variables

AppVeyor is a build software that is available on-premises or in the cloud. AppVeyor can be connected to a (public) source code repository, such as your GitHub repository, and be configured to automatically build a new version of the software whenever code in the repository is changed. The AppVeyor build configuration file (appveyor.yml) can also be checked in to a source code repository to make use of its collaboration and versioning features.

However, certain information in this appeyor.yml file might be sensitive (e.g. access credentials to other systems or services required during the build) and should not be visible to all developers (or to everyone in case of open source projects). The AppVeyor secure variables feature allows you to encrypt sensitive data before putting it into the appveyor.yml file. So only AppVeyor can decrypt this data to obtain the original value and use it during the build process. These encrypted values can e.g. be used in the appveyor.yml in configurations for environment variables or within webhooks.

The first thing to be aware of is that secure variables are only protected from users without write access to the appveyor.yml. Users with write access to this file can obtain the decrypted value. A user with write access can do this by e.g. just printing the secure variable to the build log (the secure variable is automatically decrypted by AppVeyor).

Secure Variable Encryption

We analysed properties of the encryption of secure variables.

We found out that the used cipher is a block cipher and has 128 bit (16 bytes) block size. The cipher type and the block size can be discovered by increasing the length of the plaintext. If the ciphertext length increases equally to the the plaintext length, the used cipher is a stream cipher. If the ciphertext length increases in blocks, then it is a block cipher. In the case of a block cipher, one can easily find out the block length by observing the increase in length of the ciphertext.

Furthermore, we found out that the used cipher mode is CBC. For that we performed the following test.

Our test used the following text (unencrypted) as secure variable:

Bearer SecretToken123456789012345678901234567890

The hexadecimal representation of this string is:

42 65 61 72 65 72 20 53 65 63 72 65 74 54 6F 6B

65 6E 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 30 31 32 33 34

35 36 37 38 39 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 30

When using the Encrypt YAML feature for this text, AppVeyor returns the following Base64-encoded encrypted string:

FVwaQuowgIbDmPo987vdYrmGEHeelN7l6ni8MTzouU3jtrE8/9w6tYSuq84DHJbXhMQKpxqfZOTRIH0g/flKjg==

After Base64 decoding, the hex representation is:

15 5C 1A 42 EA 30 80 86 C3 98 FA 3D F3 BB DD 62

B9 86 10 77 9E 94 DE E5 EA 78 BC 31 3C E8 B9 4D

E3 B6 B1 3C FF DC 3A B5 84 AE AB CE 03 1C 96 D7

84 C4 0A A7 1A 9F 64 E4 D1 20 7D 20 FD F9 4A 8E

Here we can already see that our encrypted ciphertext has 16 bytes more than the plaintext. This is probably due to padding and allows us infer that the block size of the ciphertext is 16 bytes.

To find out more about block size and the mode of operation, we modified the following bytes of the ciphertext:

15 5C 1A 42 EA 30 80 86 C3 98 FA 3D F3 BB DD 62

B9 86 11 77 9E 94 DE E5 EA 78 BC 31 3C E8 B9 4D

E3 B6 B1 3C FF DC 3A B5 84 AE AB CE 03 1C 96 D7

84 C4 0A A7 1A 9F 64 E4 D1 20 7D 20 FD F9 4A 8E

This ciphertext decrypted to the following text:

Bearer SecretTokL Q4▒u5i?y▒▒'15668901234567890

The hexadecimal representation of this string is:

42 65 61 72 65 72 20 53 65 63 72 65 74 54 6F 6B

4C 09 51 34 FD 75 35 16 69 3F 79 FD FD 27 31 1C

35 36 36 38 39 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 30

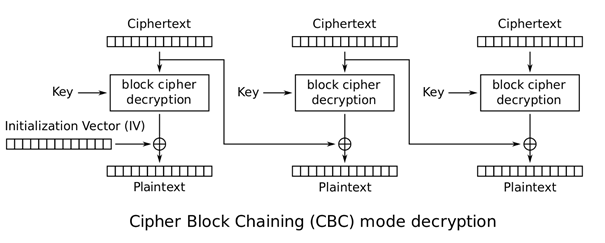

We can see that a change of the third byte in the second ciphertext block changed the whole second plaintext block and the third byte of the next plaintext block. This perfectly matches the behavior of the cipher mode CBC (as displayed in the following figure).

Generally, in CBC a change in a byte of a ciphertext block at index X directly affects all bytes of the same ciphertext block and the byte at index X of the next ciphertext block. The observed behavior further confirms that the encryption algorithm is a block cipher with 16 bytes length.

Our test didn’t lead to an error, but decrypted normally. From that we can infer that the ciphertext is not integrity protected.

In many cases missing integrity protection has security implications. In combination with the CBC cipher mode, this can result in so called “Padding Oracle” attacks. These attacks exploit

- the lack of integrity protection and

- some properties of CBC mode and PKCS#7 padding

and allow attackers to fully or partially decrypt ciphertext! This means, AppVeyor is potentially vulnerable to Padding Oracle attacks. Notably, as laid out at the beginning of the post, anyone with write access to the appveyor.yml can decrypt values by design. Thus, a Padding Oracle would have no security implications in AppVeyor anyways.

For more curious readers, we briefly describe our analysis of a potential Padding Oracle in AppVeyor.

Padding Oracle in AppVeyor

For a Padding Oracle to exist, it must be possible to distinguish the following cases (e.g. by different error message, by timing, or other means) when decrypting ciphertext:

- A given ciphertext decrypts to a valid plaintext.

- A given ciphertext decrypts to a malformed plaintext (e.g. with non-ASCII characters) and has valid padding.

- A given ciphertext decrypts has invalid padding.

This information, combined with the knowledge of the functionality of CBC and PKCS#7 and some basic logic, is enough for an attacker to decrypt most of a given ciphertext. To confirm the existence or non-existence of a potential Padding Oracle in AppVeyor, we performed the following tests.

We used a secure variable (encrypted Bearer SecretToken123456789012345678901234567890 to let AppVeyor authenticate against our web server. On the web server we received:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Authorization: Bearer SecretToken123456789012345678901234567890

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Host: 54.69.243.156:8000

Content-Length: 8858

Connection: Keep-Alive

This matches the behavior of case 1.a.

We then modified the third byte of the second ciphertext block and again let AppVeyor against our web server. This time we received:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Authorization: Bearer SecretTokL Q4▒u5i?y▒▒'15668901234567890

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Host: 54.69.243.156:8000

Content-Length: 8860

Connection: Keep-Alive

This matches the behavior of case 1.b.

Lastly, we crafted ciphertext that causes bad padding. For that we changed the last byte of the third ciphertext block. Due to CBC mode, this change should not only scramble the third block, but also change the last byte of the fourth block, which is our padding. Since padding needs to have a specific structure in PKCS#7, this change should cause incorrect padding. We used the following ciphertext:

15 5C 1A 42 EA 30 80 86 C3 98 FA 3D F3 BB DD 62

B9 86 10 77 9E 94 DE E5 EA 78 BC 31 3C E8 B9 4D

E3 B6 B1 3C FF DC 3A B5 84 AE AB CE 03 1C 96 00

84 C4 0A A7 1A 9F 64 E4 D1 20 7D 20 FD F9 4A 8E

With this ciphertext we let AppVeyor authenticate against our web server one last time. The result was:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Host: 54.69.243.156:8000

Content-Length: 8840

Connection: Keep-Alive

This matches the behavior of case 1.c.

Can this be a problem? Yes it can be! This behavior exactly matches the definition of a Padding Oracle. An attacker could now continue this attack as described in this blog post and could obtain most or all of the plaintext from the ciphertext. Particularly, if an attacker knows the initialization vector, he/she can obtain all of the plaintext. If an attacker doesn’t know the initialization vector, he/she could obtain the plaintext for the whole ciphertext except the first ciphertext block. However, in many cases the first ciphertext block can be guessed or obtained from the system.

Conclusively, in this article we showed:

- The functionality of AppVeyor’s secure variables.

- The encryption used for AppVeyor’s secure variables.

- How a small mistake in encryption could, in principle, lead to Padding Oracle attacks that allow the decryption of most or all of the ciphertext.

This post was written together with Marc Nimmerichter from Impidio. All findings were responsibly disclosed to AppVeyor and only published when we agreed that they contain no exploitable information.