Overview

All common types of code signing are based on public-key cryptography.

- Software publishers use a secret private key to sign their code

- Clients verify the signature using the public key

- Certificates connect public keys to identities

- Certificate authorities (CAs) validate publishers’ identities and issue X.509 certificates

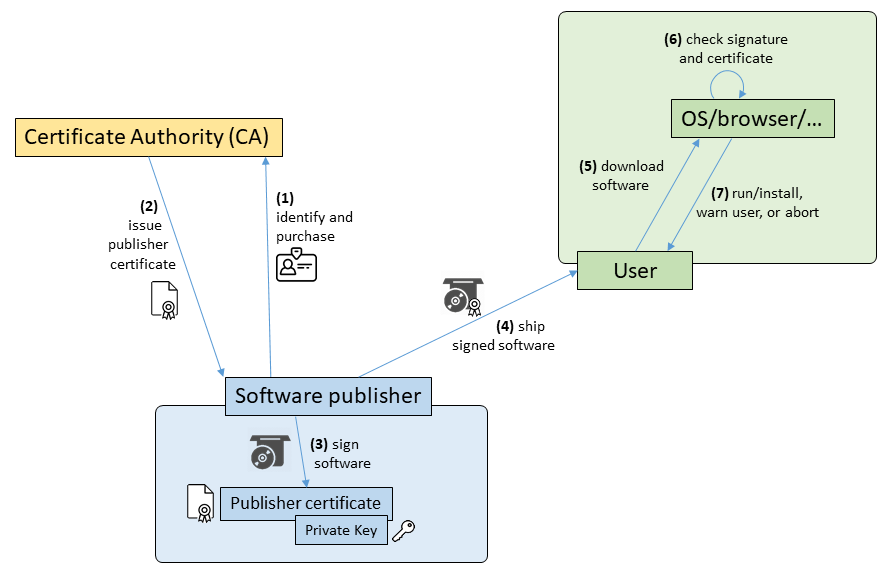

Here’s a simplified overview of the interaction between all parties:

- (1) A software publisher selects a CA to buy a certificate from. Certificates have to be renewed every one to three years, depending on certificate validity.

- (2) The CA requires the software publisher to identify using public registers, documents and/or direct contact. Methods vary between CAs and depending on certificate type (OV or EV).

- (3) The software publisher holds the private key of the certificate. Using this key, they sign every release of their software.

- (4) The signed software is shipped to users. The distribution method does not matter, since the signature is part of the distribution package.

- (5) The user downloads the software. Depending on the download method and source, different signature verification mechanisms may be triggered.

- (6) The signature will usually be verified by the operating system, Web browser, app store client, or another system such as the Java environment. Verification includes cryptographic verification of the signature and checking certificate validity.

- (7) Depending on the result of this verification, client software will take an appropriate path of action.

Signature verification usually takes place during installation or first execution. However, depending on the system and configuration, it might also be done for every single program execution.

This process can be simple in theory, but as they say, the devil is in the detail. This page tries to provide a concise summary of X.509-based code signing.

Public-key cryptography

Code Signing is based on public-key cryptography (also known as asymmetric cryptography). This method allows digital data to be signed in a secure and verifiable way.

The basic concept of public-key cryptography is that keys are always generated in pairs: a public key and a private key. The private key is only known to its owner, while the public key is known to everyone.

While most known for its use in encryption, public-key cryptography is also used for electronic signatures. It works like this:

- The signer, let’s call her Alice, uses her secret private key to sign a file.

- The receiver, Bob, knows Alice’s public key.

- When Bob receives a file signed by Alice, he can use Alice’s public key to verify that the file was signed by Alice, and that it has not been modified since.

Key distribution seems easy now: The private key must not be shared with anybody, and the public key needs no protection at all. However, this creates a new problem: How to ensure that a certain public key actually belongs to a specific entity?

The solution to this is called a public key infrastructure (PKI). PKIs issue certificates that each contain a public key and the owner’s identity. The most common type of PKI used today in general (and by all major signing platforms) is based on certificate authorities and the X.509 system of certificates.

Certificates

Public-key certificates are the corner stones of any public-key infrastructure. A certificate binds the identity of the private key’s owner to the public key. It is signed by a Certificate Authority in order to allow verification of this binding.

The most used certificate type is X.509, a certificate standard that is used for HTTPS (SSL/TLS client and server certificates), code signing, and other uses such as email (S/MIME) and PDF signing.

These certificates are technically similar, they differ mostly in key usage attributes and subject information (see next section).

Certificate contents

The following information is stored in certificates:

- Subject: The identity of the private key’s owner. The subject is provided in the form of a distinguished name. It has the following attributes:

- Common Name (CN): The owner’s identifier. For HTTPS server certificates, this is the domain name (e.g. www.google.com). For all other certificates, including code signing, this is the organization. Required.

- Organization (O): The legal name of the owner. Only required for some types, see next section.

- Organizational Unit (OU): The OU within the owner organization responsible for this key. Optional.

- Country (C), State or Province (S) and Locality (L): The specified organization’s registered location. The organization name must be unique within this location, which means that at least the country must be specified for any organization.

- Public key: The public key that matches the owner’s private key.

- Serial number: Unique number assigned by the CA. Used for revocation.

- Validity period: The certificate may only be accepted within the period specified by not before and not after.

- Issuer and signature: Name and signature of the issuing CA.

Important extensions and optional fields include:

- Key usage and extended key usage: Specifies which purposes this certificate may be used for.

- Basic constraints: Indicates whether a certificate can be used to issue certificates.

- Certificate policies: Points to CA policy documentation and indicates the type of certificate (DV, OV, EV).

- Subject alternative name: Used to list additional domain names for multi-domain HTTPS certificates.

- CRL distribution points and authority information access: Used to provide information about revocation services (CRL and/or OCSP).

Note that many of these fields use dot-separated numbers called Object Identifiers (OIDs). A reference can be found at oid-info.com or oidref.com.

Certificate types

X.509 certificates come in three flavors:

- Domain Validation (DV): The subject of the certificate is a DNS domain, such as www.google.com. Only the Common Name (CN) attribute of the subject is used. Used for HTTPS server certificates. For identity verification, proof of technical control over DNS entry or HTTP server is sufficient.

- Organization Validation (OV): The legal identity of the owner is verified using public registers, documents and/or direct contact. At least Organization (O) and Country (C) must be specified as a result.

- Extended Validation (EV): Like OV, but with additional requirements.

- Certificate authorities are required to take greater care when issuing Extended Validation certificates. The identity vetting process is more involved, and therefore EV certificates are more expensive.

- Software publishers using EV certificates are required to store their private keys on dedicated hardware, so they cannot be stolen by hackers. (For OV code signing certificates, this is only a recommendation.)

The consequences of Extended Validation differ between HTTPS and code signing:

- For HTTPS server certificates, browsers usually reward EV validation by displaying the organization’s legal name in a green box next to the URL field.

- For code signing certificates, additional trust may be assigned to EV certificates. For instance, Microsoft SmartScreen awards full reputation to new EV certificates.

(The European Union is currently working to establish a certificate system that is subject to stricter verification and carries even more legal weight called qualified digital certificates. This system defines a completely new set of rules outside the established CA landscape.)

Differences between HTTPS and code signing certificates

- HTTPS server certificates can use all types of validation (DV, OV or EV).

- Code Signing certificates always use at least Organization Validation (OV or EV).

- DV HTTPS certificates are provided for free by Let’s Encrypt. Since Domain Validation cannot be used for code signing, Let’s Encrypt does not provide code signing certificates.

- The utility of Extended Validation for HTTPS certificates is currently debated due to decreasing browser emphasis. This discussion does not apply to code signing certificates.

Certificate files

There are several file formats for storing certificates:

- DER encoded: binary encoded ASN.1 certificates and keys

- .der

- .cer, .crt (rarely used)

- PEM: Base64 encoded DER files and/or private keys

- .pem

- .cer, .crt

- PKCS#12: contain certificates and optionally private keys

- .p12

- .pfx (named after the legacy PFX format, but usually in PKCS#12 format)

- PKCS#7: signature files without signed data

- .p7b, .p7c

Certificate files can contain a single certificate or an entire certificate chain up to the root certificate. Some formats can also contain private keys protected with a password or pass-phrase.

The prevalence of files containing both certificates and private keys leads some people to think certificates contain private keys. This is not the case.

It is recommended to store private keys only on secure hardware, such as HSMs.

- If possible, use your public key to create a Certificate Signing Request (CSR). A CA can then issue a certificate based on this CSR. CAs do not need your private keys.

- We recommend that you use DER-encoded formats exclusively, since they are guaranteed not to contain private keys.

Private keys are not safe in PFX files

PFX files with private keys are convenient, but are considered insecure. Read about alternatives.

Certificate Authorities (CAs)

An issuer of certificates is called a Certificate Authority (CA). There are two common types of CAs:

- Commercial CAs are dedicated companies that verify identities and issue certificates for a fee. Commercial CAs are usually audited according to WebTrust criteria, and have their root certificates distributed with major operating systems and browsers. Their main business is issuing SSL certificates for HTTPS, but they also issue certificates for code signing, e-mail and document signing.

- In-house CAs are operated by organizations for internal use. These certificates are distributed within the organization’s network to their PCs and servers. In-house CAs use software like Microsoft Active Directory Certificate Services or OpenSSL.

CAs use their own root certificates to create new certificates. These root certificates are often pre-installed on devices (e.g. via the Microsoft Root Certificate program and Windows updates) or distributed in corporate networks (e.g. via Windows Group Policy Objects for in-house CAs).

When a CA issues a certificate, it uses its own root certificate (and the associated private key) to sign the issued certificate. Therefore, every computer that trusts the issuing CA will also trust the issued certificate.

Self-signed certificates

For testing purposes, certificates are often created ad-hoc, without use of a CA. These certificates are self-signed, i.e. they are signed with their own private key. Self-signed certificates must be trusted explicitly by the user’s system, or they will not be accepted.

Certificate chains

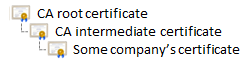

A typical certificate is issued by an intermediate certificate. The intermediate certificate is in turn issued by the root certificate. The sum of all these certificates is called a certificate chain.

A typical certificate chain looks like this:

Let’s examine this in detail:

- The CA root certificate is self-signed.

- It is well-known to the client and therefore trusted.

- The CA intermediate certificate is issued by the CA root certificate:

- Its issuer attribute is set to CA root certificate.

- It is signed using the private key corresponding to the CA root certificate.

- Some company’s certificate is issued by the CA intermediate certificate.

- Its issuer attribute is set to CA intermediate certificate.

- It is signed using the private key corresponding to the CA intermediate certificate.

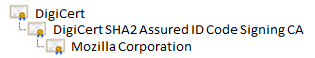

For instance, the actual certificate chain of Mozilla’s Firefox (firefox.exe) looks like this:

In order to verify the legitimacy of a signature, a client needs to know the entire certificate chain. Therefore, certificate files usually contain not only the certificate, but also every certificate in its chain of parents.

Intermediate certificates

Root certificates cannot be revoked. If there is a security problem with any of them, they must be removed from every computer. Therefore, private keys for root certificates must not be stored in systems connected to networks. Issuing an intermediate certificate is a process that is rarely performed and requires physical access to the system that stores and protects the root certificate’s private key. On the other hand, common certificates are usually issued online. This only requires access to the intermediate certificate’s private key, a far less critical resource.

Certificate revocation

Sometimes certificates are issued in error. And sometimes rightfully issued certificates are either abused, or their private keys are compromised. If a certificate authority learns of such an incident, they are required to revoke this certificate.

Each revocation has an effective date, which is often back-dated. For instance, if a publisher finds out that a certificate’s private key has been stolen two months ago, it will inform the CA, which in turn will issue a revocation effective two months ago. Signatures that were applied before this date will still be considered valid if the signature is time-stamped (see below).

Certificate revocation is an essential part of the certificate validation process. When a client encounters an unknown certificate, it must contact the certificate authority and check whether this certificate has been revoked. If a certificate has been revoked, the client will not accept signatures from past the revocation date.

Revocation protocols and reliability

The certificate contains the URL for this check, and depending on the mechanisms provided, the client can either download a full Certificate Revocation List (CRL) or check validity of an individual certificate through the OCSP protocol.

Certificate revocation for code signing is considered more reliable than revocation for HTTPS certificates. The main weakness for HTTPS certificate revocation is that an attacker who is able to mount an HTTPS attack is often already in the position to intercept network traffic to revocation servers too. This is generally not true for code distribution attacks.

However, note that Windows uses a soft revocation check policy. If the revocation server cannot be reached, certificates are accepted by default.

Time stamping

After signing a software artifact, the signature should be counter-signed by a time stamp authority (TSA). A time stamp provides proof that the signing has taken place at a certain date and time.

Each code signing certificate has a validity period of usually one to three years. Without timestamps, all signatures would be invalid after this period. Time stamps extend each signatures signature validity to that of the time stamp certificate, which is usually at least another 10 years from the time of signing.

Also, signatures would become invalid if a certificate is revoked later, even if the certificate is still considered valid for the time of signing.

Note: While the latter occurs less often, it would indirectly create a security problem: having a large number of legitimately signed binaries without time stamps would strongly discourage revocation of compromised certificates.

Certificate authorities that issue code signing certificates must also offer a free time stamping service. However, they usually apply quotas to individual client IP addresses and do not guarantee service availability, which sometimes leads to problems in automated code signing scenarios.

Always time-stamp your signatures

If your code is signed without a time stamp, all signatures will immediately become invalid if you have to revoke your certificate. This can cause considerable trouble, especially if you need to re-build and re-distribute older releases. Since this might even keep people from revoking compromised certificates, it is also a security risk.

Note that the same is true for invalid time stamps as well as for weak time stamps that will eventually be rejected by client software, such as SHA-1.

Time stamp assertions

A correct time stamp signature proves that the primary code signature was applied at a certain date and time.

The following constraints apply:

- As far as the TSA can tell, the code signature might have been applied earlier than the time stamp, but that would not matter for the purposes presented here.

- The validity of the primary signature is not confirmed by the TSA. In fact, the TSA never receives this information.

Counter signatures and TSA certificates

A time stamp is a counter-signature, i.e. the primary code signing signature is itself signed by the time stamp authority (TSA). A time stamp signature uses a TSA certificate, which in turn has a certificate chain that terminates at a trusted root certificate.

Signatures

Code Signing is performed by software publishers. They use their code signing certificates together with the matching private key to sign code they create.

Usually, the publisher is identical to the creator of the software. This can be an app author, an independent software vendor (ISV), a software contractor, or an in-house development team. Signing is usually performed either during the software build process or later, but before delivery, publishing or deployment.

Signing can also be performed by third parties, usually for code from contractors. Examples include game publishers and corporate IT departments that need to put their own signature on software created by others.

Code Signing creates the following information:

- The signature: the file’s hash digest, cryptographically signed with the private key

- The certificate containing the public key matching the private key (and its entire certificate chain)

When time stamped, the signature will be accompanied by a counter-signature, which in turn also consists of a signature and a certificate.

Signature formats

Embedded signatures

Many file formats for programs and installation packages support embedded signatures. The signature then becomes a part of the signed file. This makes handling and verification of signatures easy and reliable, during and after installation.

Embedded signature formats are used by Microsoft (Authenticode) and Apple as well as Java and Android packages.

Separate signatures

Signatures can also be stored separately from the signed files for various reasons:

- The format of the signed file does not support embedded signatures

- More than one file must be signed

- Signatures should be distributed separately from the signed files

Separate signing methods may or may not support signature verification after installation.

Examples for separate signatures are Windows catalog files (.cat) and detached signature files used on Linux (.sig).

Package and manifest signatures

Some signing methods use a combination of embedded and separate signatures.

- Microsoft Installer (MSI) uses embedded signatures for the package file, thereby implicitly signing all files within the package. However, this information is lost after installation.

- Several formats use manifest files that contain hash codes of other files. Since this often includes files that are supposed to change, such as configuration files, signatures are usually not verified after installation.

In order to get all benefits from code signing, especially post-installation verification, executable files within packages and manifests must first be signed individually.

Signature validation

A client that wants to verify a signature needs to perform several steps, all of them must succeed in order for a signature to be considered valid.

- The hash digest for the signed artifact is calculated

- All signatures and counter-signatures are validated cryptographically

- Only trusted cryptographic algorithms may be used

- The certificate must be valid

- It must have the key usage attributes necessary for the intended purpose (for example, code signing)

- The validity period must cover the current date, or, if a time stamp is present, the time stamp date

- The certificate must not have been revoked; if a time stamp is present, it must not have been revoked before the time stamp date

- The certificate must be trusted: it is either trusted by the client or the certificate chain reliably leads to a trusted root certificate

Note that some platforms use additional mechanisms to verify the reliability of a piece of software that may or may not take signature information into account. The most prevalent mechanism is Microsoft SmartScreen, a cloud-based service that assigns reputation to certificates based on global usage monitoring.

Hash digests

A signature is supposed to be authoritative for entire files, but the actual signing algorithm usually only accepts a small digest for input.

Why do we need hash digests?

- Input: The actual signing is supposed to take place within a secure system that owns (and protects) the private key, such as a hardware security module (HSM). Also, time stamp authorities (TSAs) must be called over the internet. Submitting large files to a HSM or TSA would not be a good use of resources.

- Output: If the entire file is signed, the signature would be as large as the file itself. So either the file size would double, or the actual signed file would have to be reconstructed from the signature (which is essentially the encrypted input).

The first step in all signing operations is therefore the calculation of a cryptographic hash digest. A hash algorithm generates a single number, typically from a larger binary file. This number is called digest. Any modification to the original file, no matter how small, is supposed to result in a different digest.

However, even for large digests (using many bits), there is a chance that different files may result in the same digest, which is called a hash collision. The chance of an accidental collision for a large digest is so small that it can usually be neglected. That said, a hacker might deliberately forge a file that results in the same digest as a signed one, making it possible to copy a valid signature from an existing file.

Choosing the right cryptographic hash algorithm is supposed to make this impossible with current hardware. Algorithms that are considered to be secure include SHA-2 and SHA-3. SHA-1 and MD5 were once popular, but are now considered forgeable and should no longer be used in any cryptographic context. In fact, they are increasingly rejected during signature verification.

Acceptable hash algorithms:

- Use: SHA-2, SHA-3

- Do not use: SHA-1, MD5

The most commonly used variant today is SHA-256, which is short for SHA-2 with a 256 bit digest.

Always use SHA-2 Time Stamp Authorities

Since time stamps are signatures too, they also need a hash algorithm. Many CAs provide SHA-1 and SHA-2, but SHA-1 is still the default in many scenarios.

Since time stamps are valid for many years, it’s all the more important to use SHA-2 TSAs. Consult your CA’s documentation for the correct SHA-2 URLs.